As a producer for the Miss Ohio Outstanding Teen Program and judge for other child pageants and dance contests, I have seen how “harmful dance” hypersexualizes and exploits children by wearing adult costumes, choreography, and music. I have also noticed how these imposed dance methods have affected young people later in life. Once a child receives accolades and awards for sexualized dance, they associate this learned action as a way to get further in life and become confused when they discover it is far more harmful. As a professional dancer, I encountered many hypersexualized situations in Los Angeles and New York, and someday I hope to write about them. But right now, I wanted to illustrate how a healing form of encouragement can be an asset in dance.

As a producer for the Miss Ohio Outstanding Teen Program and judge for other child pageants and dance contests, I have seen how “harmful dance” hypersexualizes and exploits children by wearing adult costumes, choreography, and music. I have also noticed how these imposed dance methods have affected young people later in life. Once a child receives accolades and awards for sexualized dance, they associate this learned action as a way to get further in life and become confused when they discover it is far more harmful. As a professional dancer, I encountered many hypersexualized situations in Los Angeles and New York, and someday I hope to write about them. But right now, I wanted to illustrate how a healing form of encouragement can be an asset in dance.

I was broken.

As I prepared to enter the dance studio and attend my first class at Wright State University, I inhaled three deep breaths and wiped my sweaty palms along my black tights. Negative self-talk rang through my head, echoing the mantra, “I’m not ready to do this.”

I was forced to return home to Ohio after an exhilarating, exhausting, and traumatic year at the University of California, Irvine. I was accepted in pre-med and awarded an athletic and academic scholarship. Before my acceptance, during high school, I was an Olympic-bound athlete sexually abused by the adults that were entrusted with my training. I silently managed to bury the four years of trauma in the deepest depths of myself and procured an “I can handle it” exterior attitude. I successfully managed my shame as I found myself landing roles in a movie-of-the-week, several school plays, and being cast on General Hospital while setting new school records in diving. Everything was looking up for me; the Olympic Trials were in three years, I was expanding my acting abilities, and I was being introduced to Hollywood. It all came to a screeching halt when one evening, an unknown graduate student decided to let his stocking and obsession manifest into an evening of traumatic abuse and discarding of my unconscious and broken body in the campus woods.

The studio door flew open as the previous class ended, and sweaty students rushed out. I had no idea that my life was about to change. With much trepidation, I walked into the space and discovered Suzanne Walker encouraging us with a welcoming smile.

Suzanne walked up to me during class and looked me in the eyes for a long time. She tilted her head, smiled, and said, “Meet me after class.” I nodded, and she walked to the other side of the room, providing corrections to the students she passed.

Suzanne leaned back, crossed her arms, and studied me. She squinted her eyes, nodded, and slammed both hands on her desktop. “So, tell me. What brought you to Wright State?”

“I don’t know what you mean,” I stammered.

“Cut the bull. I know that look in your eyes. So, tell me.” She lifted her hands as if to embrace my truth.

Nerves shot through me. “I transferred from UCI…”

“Why?”

She caught me off guard. “Well, I got sick.”

“With what?” Her brown eyes pierced into my soul.

I tried to look away.

“Look at me. Talk to me,” Suzanne said with a gentle directness.

“None of the doctors could figure it out, but I had stomach issues, was unable to keep anything down, and I lost a lot of weight.”

“What happened to cause you to get sick?” She asked without any judgment or accusation.

I was stunned and could not find the words.

“Something happened to you to cause you to get sick. Whatever it was, it’s over with. It is done. You do not need to carry it with you any longer. You can’t change what has happened, but you can change how you react to it from this day forward. You need to tell someone, or you will be trapped in this desperate bubble that will slowly destroy you.” She leaned on her elbows. “You are safe here and in the studio. Whatever is trapping you has no power here. If you believe this, you will find a way to be free. Dance is about being free, experiencing, and being in the present. Dance is fluid and expansive. Dance is about healing, tapping into your emotions, and expressing them through movement. Dance is about defying gravity and soaring without shackles.”

Tears streamed down my face.

“What is it? What has you tied up in knots?”

I divulged what I was willing to share at that time. Suzanne listened with a caring heart and an empathic ear. She encouragingly nodded as the words trickled out so she could construct and piece together the narrative. Her eyes never left mine until I broke the connection with shame and embarrassment.

“I hear you, and I believe you,” she said with a comforting voice. “Now, what do you want to do about it?”

“I don’t know,” I mumbled.

“And that’s okay. You will know what to do when the time is right. Until then, know this, you are safe here and in the studio. I’m always here for you, and I believe in you. And I will help you in any way I can. But you must do the work yourself.”

From that day forward, I found healing freedom through dance and changed my perspective from being a victim to a thriver. I proceed to take my dancing and perform on NYC stages, being a cast member of the first rival of A Chorus Line. I also originated roles for stage, television, and films.

Suzanne Walker’s encouraging words of advice remind me every day that I am not a victim. Her voice rings through my head to this day, providing me with self-confidence and the strength to help other survivors to find their truth and begin the long healing journey.

All it takes is one individual to hear you and believe your story, and this one individual can change your life.

—

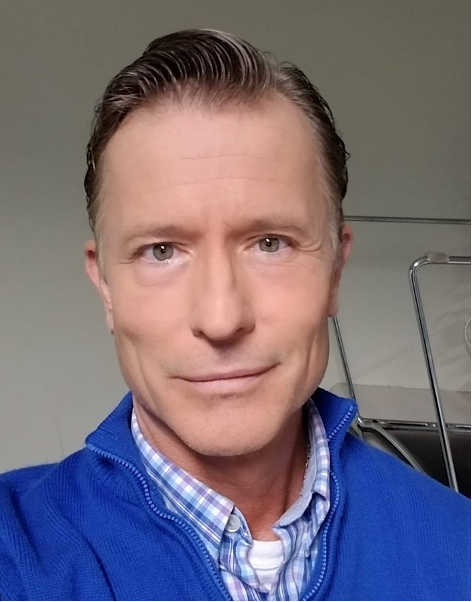

John-Michael Lander endured sexual abuse as a 15-year-old Olympic-bound athlete from the adults entrusted with his training. An empathic dance instructor helped him start on a healing path. Through writing, speaking, and consulting, John-Michael helps individuals and organizations identify the signs of grooming, manipulating, and stigma of sexual abuse and how to help survivors face the past and find their voice. John-Michael has been featured on CBC Canada Tonight with Ginella Massa, CityNews Winnipeg with Mark Neufeld, Safe Sports International, and The National Coalition to End Sexual Exploitation Global Summit. He was a voice for the #WeAreNotAlone campaign, Athletes’ Bill of Rights, and the discussion panel for the NetFlix film, Athlete A. He has published four books, including Surface Tension and Cracked Surface. He is the founder of An Athlete’s Silence and on The Army of Survivors board of directors.

John-Michael Lander endured sexual abuse as a 15-year-old Olympic-bound athlete from the adults entrusted with his training. An empathic dance instructor helped him start on a healing path. Through writing, speaking, and consulting, John-Michael helps individuals and organizations identify the signs of grooming, manipulating, and stigma of sexual abuse and how to help survivors face the past and find their voice. John-Michael has been featured on CBC Canada Tonight with Ginella Massa, CityNews Winnipeg with Mark Neufeld, Safe Sports International, and The National Coalition to End Sexual Exploitation Global Summit. He was a voice for the #WeAreNotAlone campaign, Athletes’ Bill of Rights, and the discussion panel for the NetFlix film, Athlete A. He has published four books, including Surface Tension and Cracked Surface. He is the founder of An Athlete’s Silence and on The Army of Survivors board of directors.

https://anathletessilence.com/

https://thearmyofsurvivors.org/