As a mother, dancer, choreographer, and educator I want my daughters to go to dance class to learn about their bodies, explore connections between their mind and body, and find ways to express themselves. I do not want them to learn from dance how to worry about their appearance; are they thin enough, feminine enough, sexually enticing, wearing the right make-up? Currently with a confluence of social media, televised dance shows, and the competition dance circuit (which I will define as consumer dance), dance has been reduced to a product. In this context, dance is not about feeling and sensing, but about selling oneself in the competitive dance routine, the number on the televised dance show, or in the social media post. Consumer dance is reliant on the external that is catchy and extreme because only the loud will stop the scrolling.

If a young person is learning dance, they are most likely enrolled in a private sector studio that is involved with the competition circuit (Weisbord 2010). Private sector dance schools can make money by participating in competition dance: classes, costumes, travel, and choreographic services all add up (Guarino 2014). According to IBIS World (2019), the Dance Studios industry has experienced growth from 2014-2019, with industry revenue increasing at an annualized rate of 3.8% to $4.0 billion. All are invited to participate in the competition, promoting an idea of inclusivity because of the multiple categories to enroll in, with multiple opportunities to make money. Corporations run the dance conventions (Foster 2017) and vie for the attention of young dancers. Money flows from the hopes and desires of the participants that they might become a platinum award winning dancer.

Televised dance shows such as Dancing with the Stars 2005, So You Think You Can Dance (SYTYCD) 2005, Dance Moms 2011, and World of Dance 2017 might be a young person’s first experience watching dance. Competition dance studios want to attract students so they will offer the students what they desire; dance that is fast, flashy, literal, and gendered in a competitive format—the kind of dance seen on televised dance shows. Once the young person is dancing, they are sharing and watching on social media. Young people are spending a lot of time online, thus allowing these images to be internalized and embodied. Common Sense Media reported “On average, 8 to 12-year-olds in this country use just under five hours’ worth of entertainment screen media per day (4:44), and teens use an average of just under seven and a half hours’ worth (7:22) – not including time spent using screens for school or homework.” (Rideout and Robb 2019, 3). ‘The video-sharing site YouTube – which contains many social elements, even if it is not a traditional social media platform – is now used by nearly three-quarters of U.S. adults and 94% of 18- to 24-year-olds.’ (Pew Research 2018).

Contestant after contestant competes on the competition stage, the televised dance show stage, and the internet stage strive to prove who is a “good” dancer. All three reflect hegemonic identities built upon accepted expressions of embodying gender, hetereosexual orientation, beauty, sex appeal, and fame, along with adopting the identity of what a successful dancer is in terms of body type, performance/aesthetic, and technique. Young people experience, view, and learn dance through this lens. This lens however teaches them more than dance, it teaches them about their bodies and their minds. If a young dancer views herself as an object, she does not see herself as an agent of power and change, she is acted upon. If a female dancer is valued for how she appears, she is taught to worry about how she looks. She does not own her body because she is always feeling the need to please, to modify, to alter in order to fit the industry standard. Her validity as a dancer is based largely on image and brand. The focus on the external is emphasized with the eyes of the mirror in the studio, with the eyes of the judges, and with the eyes of the virtual world. All these eyes result in the cementing of an internal judge. The consumer dance model, entwined in money and dreams, brings the body in front of the mirror to be consumed and judged by others. Creative powers are not accessed because these dancers are taught to copy and not to find their own voice.

Contestant after contestant competes on the competition stage, the televised dance show stage, and the internet stage strive to prove who is a “good” dancer. All three reflect hegemonic identities built upon accepted expressions of embodying gender, hetereosexual orientation, beauty, sex appeal, and fame, along with adopting the identity of what a successful dancer is in terms of body type, performance/aesthetic, and technique. Young people experience, view, and learn dance through this lens. This lens however teaches them more than dance, it teaches them about their bodies and their minds. If a young dancer views herself as an object, she does not see herself as an agent of power and change, she is acted upon. If a female dancer is valued for how she appears, she is taught to worry about how she looks. She does not own her body because she is always feeling the need to please, to modify, to alter in order to fit the industry standard. Her validity as a dancer is based largely on image and brand. The focus on the external is emphasized with the eyes of the mirror in the studio, with the eyes of the judges, and with the eyes of the virtual world. All these eyes result in the cementing of an internal judge. The consumer dance model, entwined in money and dreams, brings the body in front of the mirror to be consumed and judged by others. Creative powers are not accessed because these dancers are taught to copy and not to find their own voice.

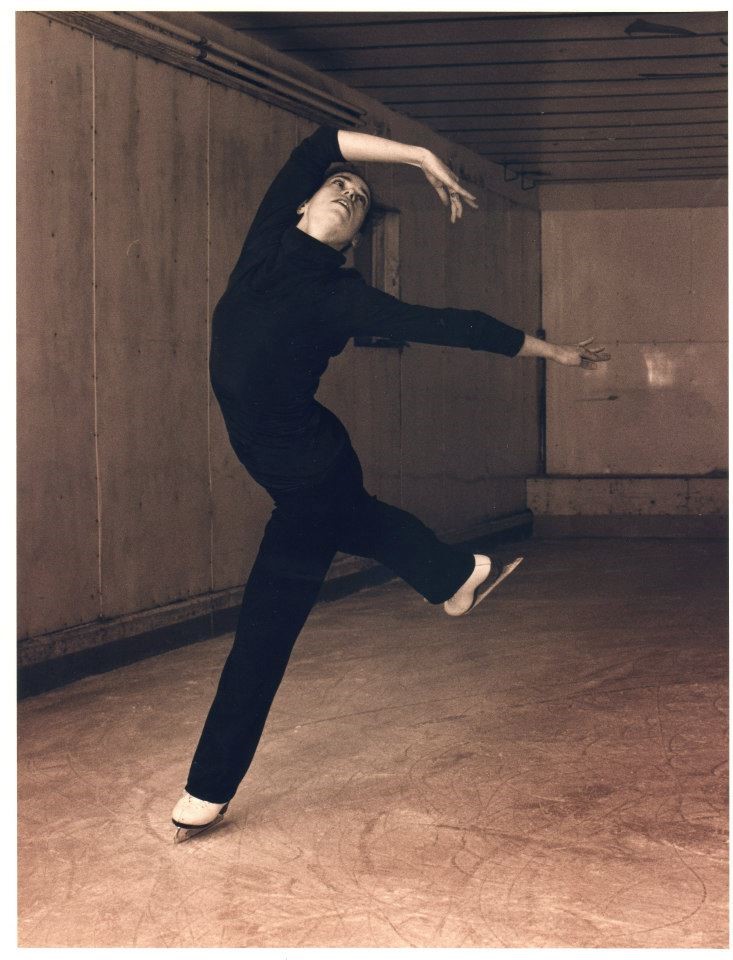

Parents should ask themselves why they are bringing their child, and most often this will be their daughter (HEADS 2018), to dance class? Is it about process or product? Is it to win? What are the themes of the choreography? How are the classes taught? What kind of movement are the students performing? A feedback loop exists between movement and the psyche; emotional shifts can occur with different movements (Shafir and Tsachor 2017). Tricks and poses that are meant to be sexual for a viewer are both inscribed onto the body and the mind. Is the student internalizing the idea that her worth is based on her appearance? The dance studio can be a place to find empowerment through movement (Harrington 2019) and it is up to the parent to seek out a studio that views dance not as a beauty pageant but as a place to find growth, critical thinking, and creativity. The money-making model is the competition circuit, and the studios that do not participate are in the minority. If the current trends are not addressed, recognized, and countered, dance itself will change in its meaning, pedagogy, performance, and appreciation. Growing up as a competitive ice skater, I know how a discipline can become solidified in how it is taught, performed, and appreciated. The dance studio can be a place of transformation and change, let us fight to hold space for this vision.

Parents should ask themselves why they are bringing their child, and most often this will be their daughter (HEADS 2018), to dance class? Is it about process or product? Is it to win? What are the themes of the choreography? How are the classes taught? What kind of movement are the students performing? A feedback loop exists between movement and the psyche; emotional shifts can occur with different movements (Shafir and Tsachor 2017). Tricks and poses that are meant to be sexual for a viewer are both inscribed onto the body and the mind. Is the student internalizing the idea that her worth is based on her appearance? The dance studio can be a place to find empowerment through movement (Harrington 2019) and it is up to the parent to seek out a studio that views dance not as a beauty pageant but as a place to find growth, critical thinking, and creativity. The money-making model is the competition circuit, and the studios that do not participate are in the minority. If the current trends are not addressed, recognized, and countered, dance itself will change in its meaning, pedagogy, performance, and appreciation. Growing up as a competitive ice skater, I know how a discipline can become solidified in how it is taught, performed, and appreciated. The dance studio can be a place of transformation and change, let us fight to hold space for this vision.

References

Foster, S. L. 2017. “Dance And/as Competition in the Privately Owned US Studio.” In The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Politics, edited by R. J. Kowal, G. Siegmund, and R. Martin, 53–76. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Guarino, Lindsay. 2014. “Jazz Dance Training Via Private Studios, Competitions, and Conventions.” In Jazz Dance: A History of the Roots and Branches, edited by Lindsay Guarino and Wendy Oliver, 197–206. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

Higher Education Arts Data Services, HEADS. 2018-19. Dance Annual Summary, Reston, VA: National Association of Schools of Dance.

IBIS World. 2019. IBIS. Updated December 31, 2019. Accessed Nov. 23, 2020. https://www.ibisworld.com/united-states/market-research-reports/dance-studios-industry/

Pew Research. 2018. https://www.pewinternet.org/2018/03/01/social-media-use-in-2018/

Rideout, Victoria and Michael Robb. 2019. “THE COMMON SENSE CENSUS: Media Use By Tweens and Teens.” Common Sense. https://www.commonsensemedia.org/sites/default/files/uploads/research/2019-census-8-t o-18-key-findings-updated.pdf

Shafir, Tal, and Rachelle P. Tsachor. 2017. “A Somatic Movement Approach to Fostering Emotional Resiliency through Laban Movement Analysis.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 11. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00410.

Weisbrod, Alexis A. 2010. “Competition Dance: Redefining Dance in the United States.” Doctoral diss., University of California, Riverside.

by

by